Bloomberg blamed the end of 'redlining' for the Recession. Not only is that wrong, it’s racist.

Oligarch Michael Bloomberg claimed the 2008 collapse was caused by the end of “redlining,” a practice that denied the poor and minorities mortgage capital for decades. He's not telling the truth.

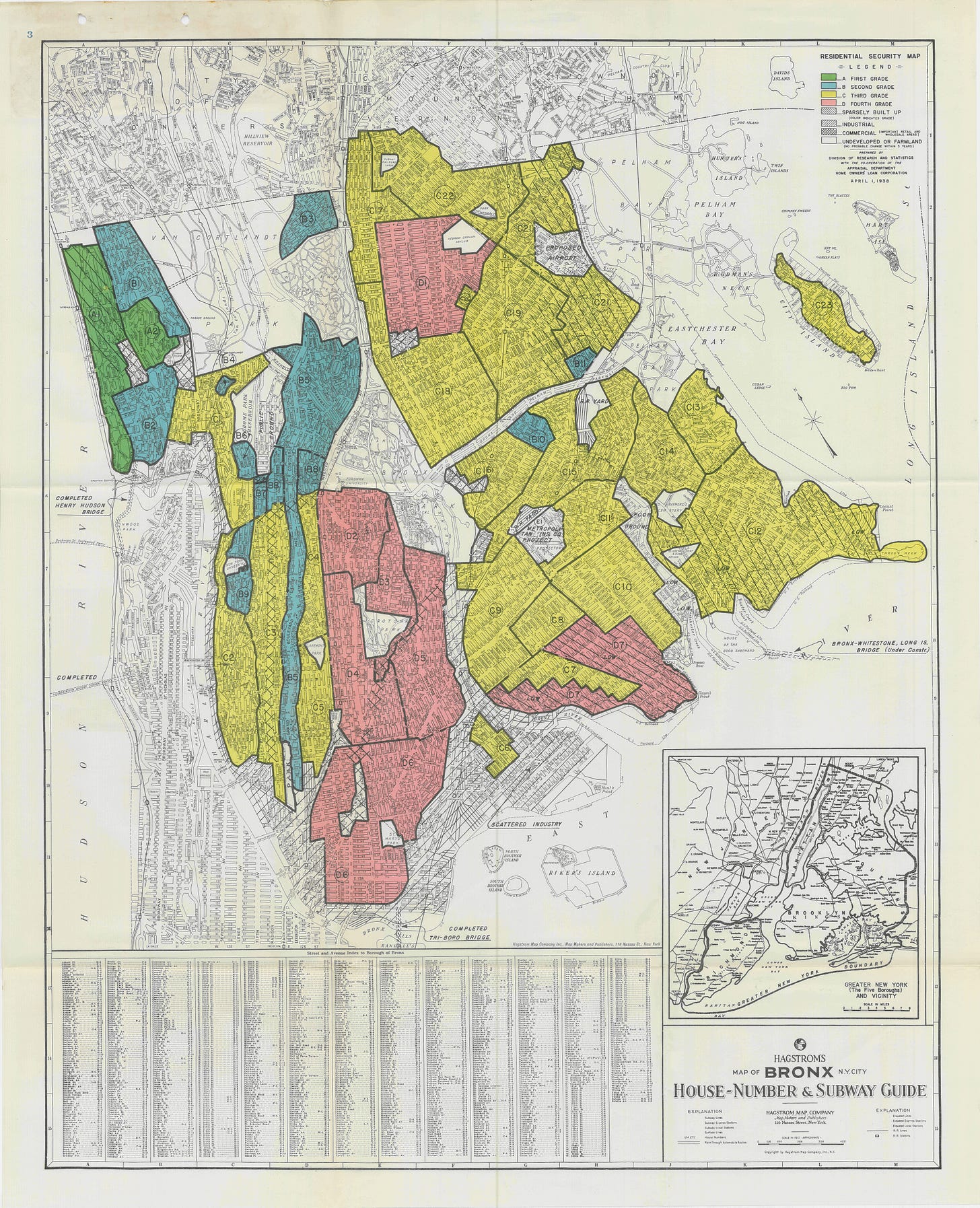

Photo Illustration by Aaron Mayorga. Photos by Getty; Perla de Leon; and the University of Richmond via HOLC.

Welcome to Terminally Chill—a newsletter that discusses sports, politics and other issues from a left-wing perspective—by Aaron Mayorga, an award-winning freelance writer and photojournalist.

TWO DAYS AFTER the collapse of Lehman Brothers, with the global financial system fast approaching meltdown, then-New York City Mayor and current presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg traveled to the nation’s capital for an appearance at Georgetown University, and offered an ahistorical, and profoundly racist, claim regarding the cause of the Great Recession.

According to the billionaire mayor, the seeds of the crisis were sown in 1977, when Congress enacted the Community Reinvestment Act—a bill aimed at ending “redlining,” the discriminatory practice of denying loans and mortgages in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

That, Bloomberg contended in a video that’s recently gone viral, was a mistake.

“It all started back when there was a lot of pressure on banks to make loans to everyone,” he told university president Dr. John DeGioaia and a gathered audience. “Redlining, if you remember, was the term where banks took whole neighborhoods and said, ‘People in these neighborhoods are poor, they’re not going to be able to pay off their mortgages, tell your salesmen don’t go into those areas.’”

Following the Congress’ intervention in the mid-70s, Bloomberg said of ending redlining, “And once you started pushing in that direction [to lend in low-income and minority communities], banks started making more and more loans where the credit of the person buying the house wasn’t as good as you’d like.”

Just as Jacobin magazine’s Luke Savage said of Pete Buttigieg’s defense of his 40 billionaire donors, Bloomberg’s attempted defense of redlining is simply Orwellian.

As economist Robert Gordon explains, blaming the CRA for the crash is a right-wing talking point. “Half of subprime loans came from those mortgage companies beyond the reach of CRA,” Gordon notes. At most, only a quarter of subprime loans came from banks under the auspices of the 1977 law, while “the worst offenders, the independent mortgage companies, were never subject to CRA -- or any federal regulator.”

Moreover, counter to long-held assumptions by lenders and banks, there’s little indication that providing home loans to low-income folk and people of color are risky investments. A week after Bloomberg’s Georgetown remarks, the New York Times found that the Nehemiah housing program, which built and sold 3,900 single-family homes in the Bronx and Brooklyn, had a default rate “that is close to zero.”

And, contrary to the oligarch’s revisionist history, redlining was more than simply banks and lenders telling their salesmen to avoid certain neighborhoods; rather, it was the deeply racist, classist and systemic withholding of capital from communities of color, which would eventually lead to a cascade of disastrous consequences—ranging from blockbusting, urban decay and planned shrinkage in many of America’s inner-cities.

Officially, redlining has its roots in the New Deal: in 1934, with the nation mired in the Great Depression, the Roosevelt administration created the Federal Housing Authority, an agency tasked with stabilizing the housing market and ensuring homeowners avoid foreclosure. However, the creation of the FHA also came with it the codification of the already-existing discriminatory and segregative standards by which banks and others were assessing real estate risk.

A year later, Home Owners’ Loan Corp., another New Deal creation, surveyed more than 230 cities and created a set of maps by which loan officers could quickly judge the credit-worthiness of a given neighborhood.

These “residential security maps” were color-coded—green areas represented the safest investments with blue areas slightly less favoured, while places in yellow and “red” were generally considered non-viable and “hazardous” for investment. In creating them, HOLC cartographers used the racial makeup of an area as an underlying basis by which they determined a neighborhood’s rating.

For example, near Crotona Park in the Bronx, HOLC concluded the neighborhoods of Tremont and Morrisania were undesirable investments, largely on the basis of a “steady infiltration of negro, Spanish and Puerto Rican into the area.” Meanwhile, in Central Harlem, the surveyor there wrote, “Formerly a good residential district with many well built private homes. Now practically entirely Negro with many tenements.”

Both neighborhoods were, as a result, redlined.

These aren’t aberrations, either. According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, approximately two-thirds of redlined neighborhoods are minority neighborhoods, while more than three-quarters are low-income. Furthermore, in The Possessive Investment in Whiteness, sociologist George Lipsitz found that between 1934 and 1962, less than two percent of $120 billion of federally-subsidized housing money went to non-white families.

While mostly-white and well-off neighborhoods in cities across the country, including New York, benefitted from a reliable and steady stream of mortgage capital, redlined nabes fell into disrepair and were deliberately neglected by private industry and all levels of government.

This strategy was ominously called benign neglect—the effective triaging of municipal resources from “dying” minority and low-income neighborhoods to whiter, wealthier and “healthier” ones. In the most infamous case, during the late 1960s and the 1970s, city officials, in consultation with the RAND Corp., began closing fire stations in the South Bronx, as a function of improving service elsewhere without increasing spending.

By 1976, more than 300 fires burned there daily, and many were started at the behest of landlords, hoping to cash-in on the six-figure insurance policies they’d taken out on their properties. “Slumlords hired rent-a-thugs to burn the buildings down for as little as $50 a job, collecting insurance premiums of up to $150,000,” recounts Jeff Chang in his book about hip-hop Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop. “Insurance companies profited from the arrangement by selling more policies. Even on vacant buildings, fire paid.”

By decade’s end, about two-fifths of the South Bronx’s housing stock had burned.

A year later, the Community Reinvestment Act was passed with bipartisan support, and signed into law by President Jimmy Carter—officially putting an end to redlining. Still, wealth inequalities and other disparities remain: among others, redlined communities are, on average, five degrees Fahrenheit warmer than non-redlined ones; they generally have worse air quality, and a higher incidence of asthma, and suffer from an inadequate number of bank branches, prompting residents to become reliant upon pawn shops and check-cashing places to fill the financial services void.

Michael Bloomberg knows this history: He was Mayor of New York City for more than a decade, after all, and he first moved to the city in 1973, just as the bottom started to fall out in the South Bronx and elsewhere in the outer boroughs. Yet that he’d rather scapegoat poor and minority communities (and not, you know, the bankers and derelict regulators responsible) for the largest financial collapse since the Great Depression shouldn’t come as a surprise.

In fact, it’s consistent with the billionaire plutocrat’s worldview: that working-people, especially those of color, needn’t be trusted and, instead, ought to be saved from their own desires, by a technocratic and overbearing nanny-state; that the problem isn’t an economic and political system that leaves elites to their own avaricious and exploitative devices, but is everyday people exercising what little agency they’ve left.

It’s a self-serving belief: one that excuses the injustices of the capitalist institutions Bloomberg and others billionaires are so desperate to defend, while also justifying the creation of the paternalistic state that he, personally, so eagerly seeks to helm. It masks that, contrary to his electoral pitch, Bloomberg too is beholden to a so-called special interest—his massive $60 billion fortune. It allows him to elude personal blame and accountability for his racist record, yet enables him to rebrand as a benevolent sage who just wants to “protect people from themselves.”

But reality tells a much different story. In Bloomberg’s world, the best use of government resources are oriented towards policing the day-to-day habits of workers, and punishing them if any step out of line.

Why else would Bloomberg have said in April 2018, at an International Monetary Fund event, that regressive taxes on the poor are good? “That's the good thing about [regressive taxes] because the problem is in people that don't have a lot of money,” the former mayor told IMF president Christine Lagarde. “And so, higher taxes should have a bigger impact on their behavior and how they deal with themselves.”

Why else would he have said that stop-and-frisk—which essentially gave police carte blanche to unconstitutionally racially-profile and harass hundreds of thousands of innocent, young black and brown New Yorkers on the street—was justified? “Ninety-five percent of murders, murderers and murder victims fit one M.O. You can just take a description, Xerox it, and pass it out to all the cops,” he told the D.C.-based think tank Aspen Institute matter of factly. “They are male, minorities, 16 to 25. That’s true in New York, that’s true in virtually every city.”

Why else would he have suggested that the city’s more than 400,000 public housing residents—90 percent of which are either black or Latino—ought to be fingerprinted as a means of keeping crime down? To make matters worse, the privacy-eroding suggestion came despite the fact that (A) the lobbies of many NYCHA tenements have broken door locks that allow would-be criminals access, and (B) he hasn’t acknowledged “the mismanagement and resultant cover-ups at NYCHA during his tenure that led to a dramatic deterioration of living conditions… [and] the appointment of an oversight monitor,” according to The City.

If he’s successful in buying his way to the White House, addressing the roots of inequality will be consistently forgone in favor of disciplining the marginalized with the harshest and cruelest measures possible. Bloomberg’s comments on redlining, as well as the other statements above, are yet another reflection of his draconian governing ethos—and the lengths to which he’s willing to minimize and lie about real human suffering to justify it.

For that reason, among countless others, Bloomberg and his oligarchic pursuit of the presidency must be defeated.